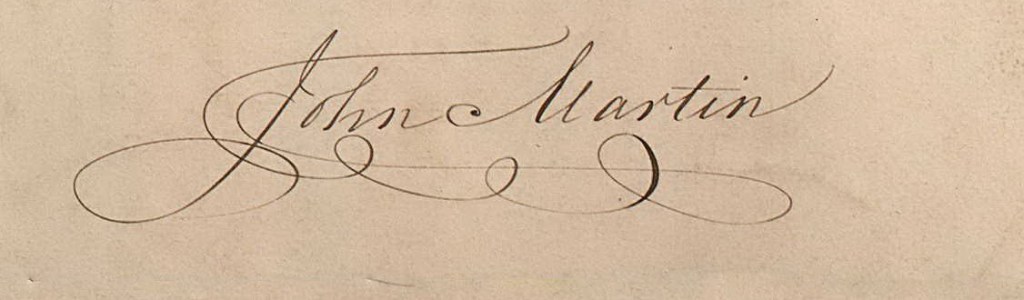

This website is devoted to the life and work of a single man, a nineteenth century land surveyor from Dorset [England] called John Martin. Although he is no relation of mine I became interested in him after discovering a series of diaries he wrote and which are now stored safely in the Dorset History Centre in Dorchester. A further four diaries are known to exist in private hands, including the one for 1863, the year in which he died, but these are not available for study.

If the focus of the website is a single man, it’s purpose has changed and grown bigger since I started it. Through the pages on the site I seek to tell stories. Firstly of course it is the story of John Martin, his family, his work and his role in the local community but it is the story also of a rural England that has disappeared for ever. An England that was ordered and arranged by customs and practices some of which are recorded here. Then there are the stories of some of the many villages and hamlets that Martin worked in and which he helped to transform. Lastly it tells the story of some of the people who John Martin encountered. He can on occasion be found conversing with Peers of the Realm in the morning and dung hauliers in the afternoon.

Martin was baptised in May 1780 and died in 1863 at the age of 83. This was a pivotal period in the history of the country during which the rural landscape was quite literally transformed. A time traveller leaving Dorset in, say 1760 and returning in 1860 could not have failed to observe the physical changes in the appearance of the Dorset countryside. Delving deeper, he or she would have noted social changes too. In many parishes, seemingly overnight, customs, laws and agricultural practices that had evolved over centuries and which had glued the community together, were abolished. In 1834 that most basic responsibility of the community, the care of it’s poorest inhabitants, was transferred away from the parish to ‘The Union’, and it’s workhouse.

Driving the transformation were three great movements with which Martin was intimately involved. The first was the inclosure movement, designed to inclose [their word], with fences, the large open fields and commons that had once been a feature of the Dorset landscape. The results of inclosure, the picturesque fields and hedgerows that we see today, had devastating consequences for a particular class of ‘yeoman farmers’ who being deprived of the common were reduced to the status of agricultural labourers. With a rising population, and no alternative occupations to turn to, Dorset farm labourers were ‘ten a penny’ and had the dubious honour of being paid the poorest wages in the country.

Then there were the turnpike trusts that from the mid 18th century had gradually improved the country’s roads. The revolution here was not so much that you could travel further, or to new places, but that you could do so faster and at all times of the year. Finally, during the 1840’s and 50’s, the railways arrived in Dorset. For the first time man could travel faster than he could on a galloping horse. Like two large armies the London and South Western Railway and the Great Western Railway carved their way through the countryside in their attempts to gain territory and outflank each other. Nothing like it had been seen before and John Martin was there and involved with it all.

Martin’s most enduring legacy though came about because of an even more revolutionary change in society, when the balance of power and influence between church and state was subtly altered. For over 900 years the church had claimed, by divine law, a tenth part of each farmer’s annual produce. It was a contentious tax though and in one author’s view the avarice of the Church of England brought it close to being disestablished. From 1836 this tax, the tithe, as it was known, was replaced by a monetary payment that was regulated, not by the church, but by the state. This process, known as Tithe Commutation required land surveyors to make large scale maps of the parishes of the counties and John Martin made over fifty of these in Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire. He was the most prolific of all the Dorset land surveyors.

I have structured the website in a manner similar to a traditional text book. The menu bar has a number of section headings and a brief description of the various topics is given there. Clicking on the + sign next to these headings will call up the drop down menus representing the chapters. None of the text is copyrighted so may be used freely elsewhere although an acknowledgement of it’s origins [by way of a link to johnmartinofevershot.org ]would be appreciated.

On the “In Depth” page I look in greater detail at some of the history and stories that lay behind the entries in his diary. I hope you find the site interesting. If you have any questions about Martin or any of the topics covered please feel free to email me at johnmartinofevershot@gmail.com

Website updated 22/01/2026

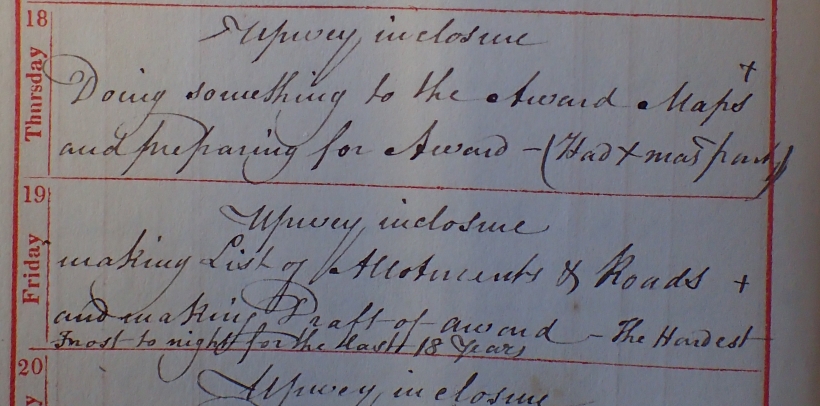

John Martin’s Month – January 1838

It is difficult to know how John spent his Christmas’s. All he ever writes is that he was “At Home”. Even though he was a churchwarden he never mentions going to church or gives any details of the services which were held.

What kind of party was it? It was probably not as boring as we might think and may even have been the ‘Evershot Ball’ which was held around this time. The Salisbury and Winchester Journal a year later gives an account of it: An ‘assemblage of ladies and gentlemen’ totalling some seventy in number came from Dorchester, Sherborne, Bridport, Beaminster, Crewkerne and Langport. They quite literally danced the night away and did not leave until ‘near seven in the morning’. Such late nights or early mornings were not uncommon in the countryside, no doubt it would have been dangerous for horses and carriages to travel over the rough country roads of the time.

In 1839 the ball was organised by the Jennings and Jesty families who were intimately connected with Martin. Whether he went on that occasion is not unknown. His wife had been dead less than a year and he may not have thought it appropriate.

It seems that every day we are told that some weather record or another has been broken. These are of course based on ‘official’ records but old diaries, and not just John Martin’s , are full of entries relating to extreme weather events. Some are much more dramatic in their effects. In 1773 there was a storm that was so violent that it blew a wagon off the bridge at Child Okeford drowning the four horses that were hauling it.